A System On The Brink

Health has become this country’s greatest fiscal liability. But it’s also this country’s greatest growth opportunity. Reform is not just about avoiding decline.

It’s about building a path to prosperity.

Reforming A Leviathan

The healthcare ecosystem in the UK is vast. As of 2025 in England alone, there were 202 NHS Trusts, 42 Integrated Care Boards (ICBs), and nearly 1.4 million full time staff in the NHS.

Then there is the DHSC, the devolved nations, local authorities, more than 20 government agencies & public bodies, and collaborating private providers like GPs, Dentists, Hospitals, and Social Care. All of these actors collaborate with one another in the jumbled back end of the health system, in order to produce the clean facade of a 'free at the point of use' front end.

We don’t really have a National Health Service. We have an enormously complex industry pretending to function under one brand.

Foreword

“What goes too long unchanged destroys itself. The forest is forever because it dies and dies and so lives.”

Ursula K. Le Guin

At the turn of the 20th Century, life expectancy in Britain was approximately 45.

For at least half the millennium that proceeded, it fluctuated little between the bounds of 35 and 40.

Between 1550 and 1800, maternal mortality was experienced by 1 in 18 married women. In 1900, there was a 15% chance that a newborn would die before reaching their fifth birthday, accounting for a third of all deaths. Today, this makes up significantly less than 1% of all deaths. This was caused by the likes of measles, tuberculosis, diphtheria and dysentery, which are now, fortunately, much rarer and significantly less fatal, thanks to improvements in public hygiene and vaccinations.

Can you imagine visiting the world of 1900?

Contemplate, for a second, Britain in the dying embers of the Victorian Era. Having reaped the economic benefits of the Industrial Revolution, life expectancy was only 5 years longer than it was in 1836 at the start of Queen Victoria’s reign. Predicting, then, that life expectancy would basically double in only a handful of generations, despite the bloodshed of two World Wars, would certainly have been ridiculed.

Yet, today, our experience with the health system is not one of miracles, as it ought to be, but one of malaise. Far from a well oiled engine of growth, the health system appears to have stalled - but is somehow still guzzling fuel.

In 2024/25, the OBR forecast that total government spending would amount to over £1.27 Trillion, of which £201.9 billion or nearly 16% would go to the health budget (the second largest budget, behind only welfare).

But the health budget itself is far from a comprehensive representation of what we actually spend on health.

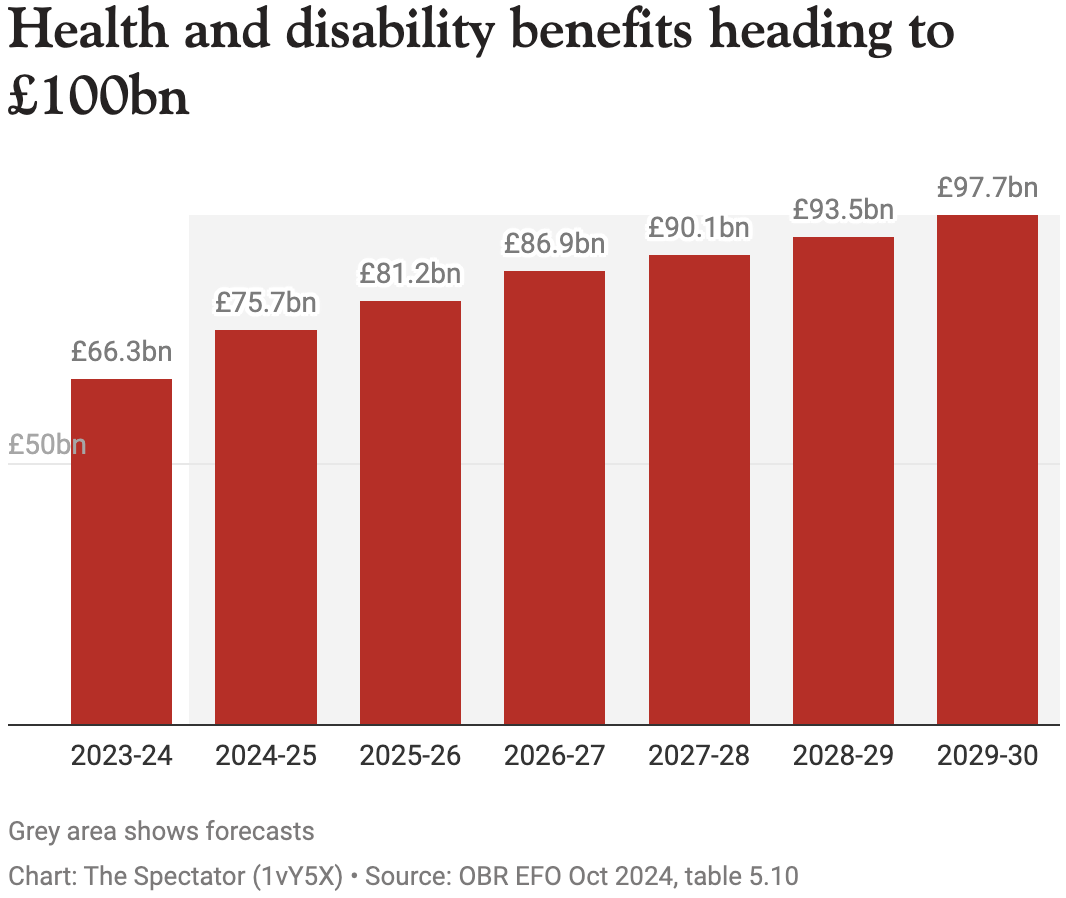

In addition, local authorities in England alone were projected to spend £38.6 billion on social care and £3.9 billion on public health. The devolved nations were projected to spend a further £40 billion combined on their respective health systems (Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland). Then there is the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), which was forecast to spend over £75 billion on health and disability benefits. This is now projected to increase to nearly £100 billion by 2030, which will then account for roughly 8% of total government spending, £66 billion of which will be for working age claimants.

Then, of course, there is the private sector. According to the Association of British Insurers (ABI), 5.8 million people had some form of health cover in 2022, either individually or through their employer. Moreover, personal out-of-pocket spending on health totalled a whopping £40.4 billion in 2023.

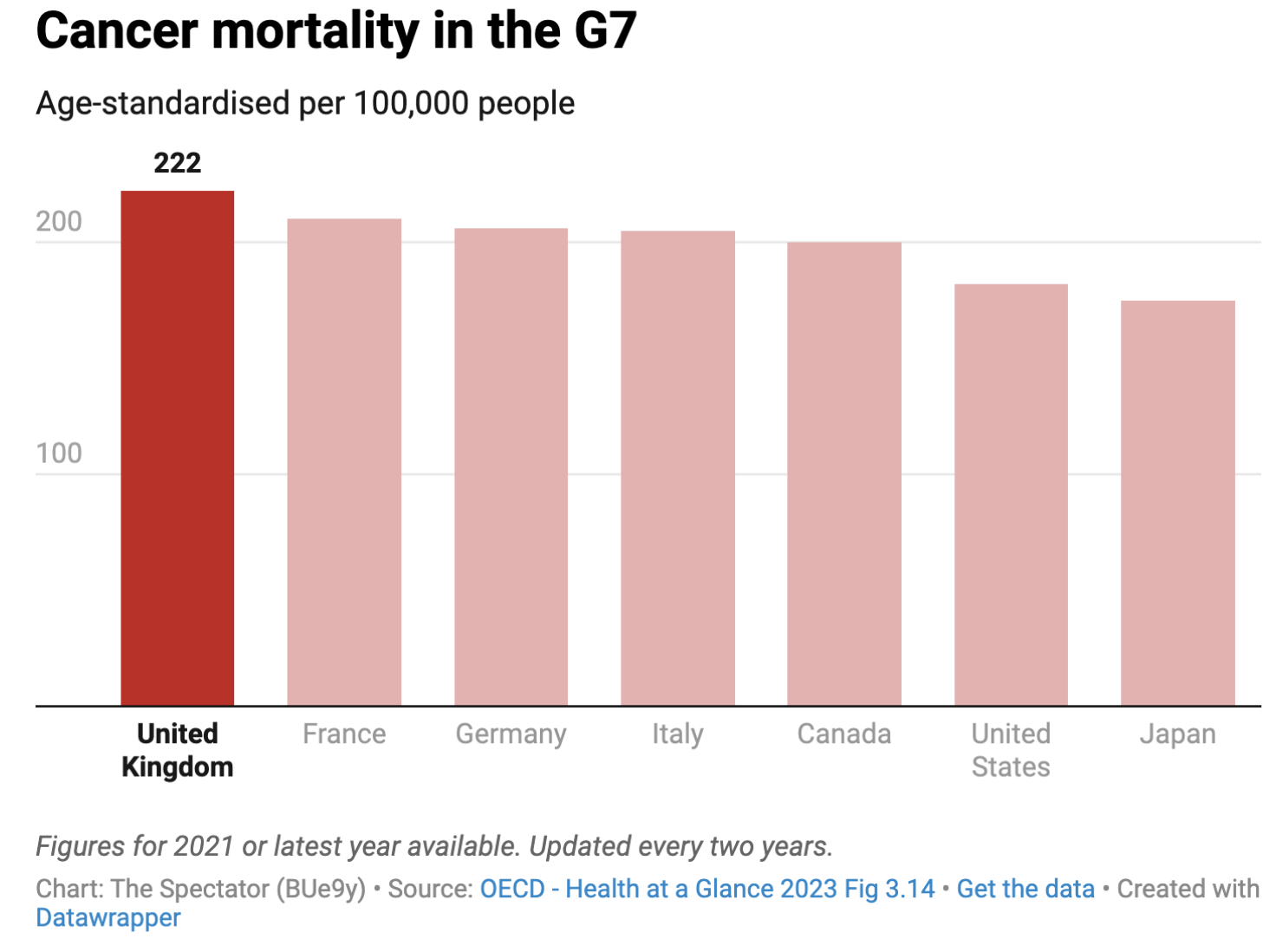

So what do we get for all this spending?

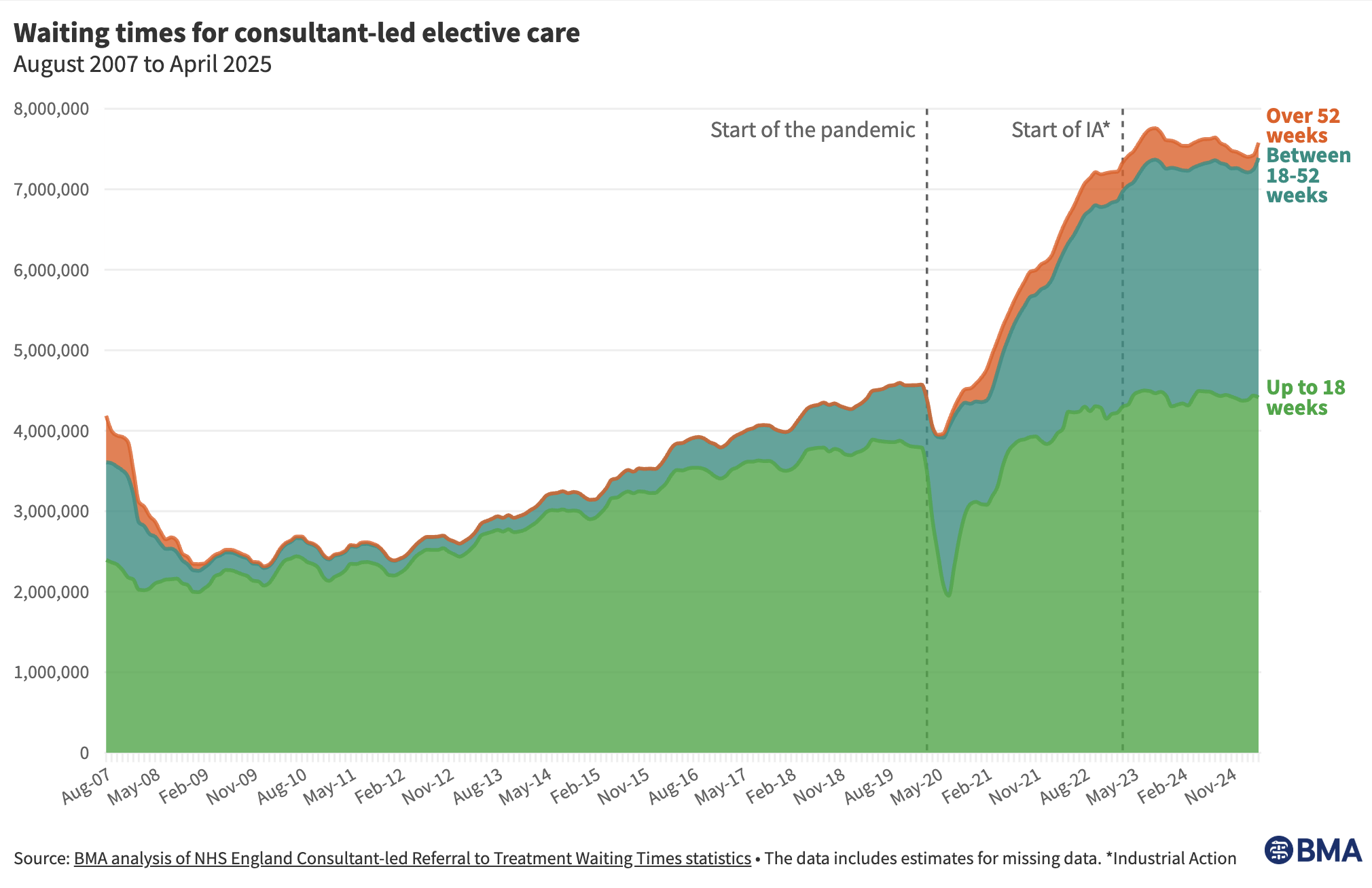

According to the ONS, public service health productivity was 18.5% lower in Q3 2024 than in Q4 2019. Since the Financial Crisis in 2008, waiting lists have roughly tripled and the proportion of people aged 16-24 registered as out of work, because of long-term illness, has grown over 2 and a half times from 3.6% to 9.3%. In February 2025, 86% of NHS staff said the service was in either a ‘fairly’ or a ‘very weak’ state.

Despite a worsening service, the health budget has been increasing at an unsustainable rate, expanding by over 40% in real terms since 2010/11, whilst real GDP has grown by less than 25% over the same period. Few realise the NHS has had over triple the ‘£350 million a week’ Vote Leave promise since the referendum, increasing in real terms from under £2.7 billion per week in 2016/17 to nearly £3.9 billion per week in 2024/25.

Health has become this country's greatest fiscal liability.

But it is also, in my opinion, this country's greatest growth opportunity.

Health and prosperity are inextricably linked, with multiplier effects in both directions. Since life expectancy was 45, real GDP Per Capita has increased more than fivefold.

But life expectancy has now stagnated, and the number of years spent ill is increasing. It’s an issue we can’t afford to ignore, yet our health system remains intransigent. Now, fewer than 1 in 5 of the public believe the NHS will get better.

It doesn’t have to be like this.

For the first time in perhaps a generation, we have a government that has publicly acknowledged this. Wes Streeting declared on the 5th July 2024 "from today, the policy of this department is that the NHS is broken."

Then in their recently published 10 Year Health Plan, they said “the choice for the NHS is stark: reform or die.”

Now in fairness to the government, it’s much harder to write these plans than it is to criticise them. But then it’s also much harder to deliver these plans than it is to write them. Whilst the plan is big on ambition, in many places it’s small on detail.

Nevertheless, some of their announcements are very welcome. The establishment of neighbourhood health centres could be transformational if they end up like Washwood Heath community clinic. Their goal for the NHS app has the potential to drastically improve our interactions with the health service, if they can deliver such an everything app. They even teased the idea of letting Trusts retain budget surpluses, although that is dependent on transitioning them all to Foundation Trusts. But in combination with the commitment to link future funding to performance, with provider league tables, it’s fair to say the government is attempting to improve internal incentives for fiscal responsibility.

However, at its worst points, the plan reveals the state’s interventionist tendencies and its lack of self-awareness, identifying the right problems but clunkily allocating the wrong solutions:

-

They plan to further restrict the advertisement and sale of junk food and alcohol. They will mandate that supermarkets share their sales data, and will fine them for failing to sell enough healthy food. They’ll even look to establish a ‘reward scheme’ to incentivise the public to make healthier choices. People don’t need you to set up a reward scheme. The government won’t do better than Darwin. There is a saying in advertising: a good offer can overcome a bad campaign, but a good campaign can’t overcome a bad offer. People don’t buy junk food because of the advertisement. It’s because four breaded ‘chicken steaks’ cost £3.60 at Tesco, but organic chicken breasts of the equivalent weight cost £11.48. If you want to tackle obesity, then the government should undertake some serious self-reflection about the role it plays in making it so difficult to produce healthy food cheaply in this country.

-

They set a target to reduce overseas recruitment from 34% down to 10% by 2035, but their solution is to give domestic applicants a ‘priority’ in the recruitment process. According to the BMA, between 15,000 and 23,000 doctors left the NHS prematurely in 2023 alone. Meanwhile, only 7,800 government funded medical school places are available for the 2025/26 academic year. In 2024/25, there were over 24,000 UCAS applicants for medicine. Then there is a further bottleneck for speciality training places. Last year, there were fewer than 13,000 posts but over 25,000 unique applicants. The plan commits to create 1,000 new specialty training posts over three years, but more than 20,000 are expected to miss out this year. Not all of that number are domestic applicants, but we are talking about medical graduates, who have completed two years of foundation training, going unemployed because there isn’t enough speciality training capacity.

-

The plan claims that 26,000 to 38,000 people die in England every year due to their life-time exposure to pollution. But their new solutions include investing in bike lanes, encouraging active travel, and launching a consultation on how to reduce emissions from ‘domestic burning’. Instead, the government should pass the LFG Infrastructure Bill, so that we can start to build an effective public transport system fuelled by abundant sustainable energy production.

Ultimately, the plan pins a lot of hope on technology, which is an ambition I can fervently salute. This is a time of immense technological development. We should be more optimistic than ever before about what is possible in healthcare, as artificial intelligence begins to accelerate drug discovery, revolutionise diagnostics, and help build tailored preventative care. We have the potential to unleash progress at a velocity that will make the Industrial Revolution look sluggish. In an interview with CBS, Sir Demis Hassabis recently posited that AI could help to cure all diseases within the next decade.

However, we are talking about the same organisation that remained the world’s largest buyer of fax machines at the start of the Pandemic. A mere 30 years after the invention of the World Wide Web. In their own words, the NHS is a “20th century technological laggard”, so an element of skepticism is advised when imagining them getting the most out of frontier capabilities.

To their credit they’ve committed to build a Single Patient Record, but to this day some Trusts still use paper records despite the fact Electronic Patient Records first launched in 2002. The underlying technology is not enough; they need a thorough plan for delivery. How will they recruit the skills to build new technological systems? Will collaborating private providers be able to integrate with them? How will they ensure NHS wide adoption throughout primary and secondary care?

More importantly, what happens in the meantime?

NHSE won’t be integrated into the DHSC for two years.

The 10 year Health Plan included no tangible policies for social care, and their independent review will not report back until 2028. Meanwhile, 1 in 7 hospital beds are taken up by ‘bed blockers’ who are stuck in hospital despite meeting clinical standards for discharge, due to poor flow management and a lack of alternative provisions like social care.

Whilst preventative care might improve the strain on acute services in the long run, we need to get a grip immediately on one of the biggest causes of avoidable deaths - A&E waiting times.

The NHS has an estate that is literally crumbling, with a maintenance backlog of £13.8 billion, and a workforce resorting to industrial action… again.

Enough is enough. This blog will serve as a research and policy programme database, to set the foundations for action.

Finally, to the 80% of Brits who don’t think the NHS will get better, to those who believe the NHS must stay the same, and to those who are resigned to decline, I say: think back to 1900.

What is inconceivable today can become insignificant tomorrow.

Funding Model

“Show me the incentive, and i’ll show you the outcome.”

Charlie Munger

-

Parliament's Public Accounts Committee recently reported on NHS financial sustainability:

"The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) and NHS England (NHSE) seem complacent regarding the NHS's finances … Both DHSC and NHSE tend to blame the NHS's poor financial position on exceptional external factors ... [but] there are also well-known issues that are within officials' control."

The funding and budgeting model in the health system is an administratively burdensome web that incentivises needless waste.

"The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) has overall responsibility for healthcare services in England, and for their financial management and sustainability. NHS England (NHSE) receives funding from DHSC to deliver health services and passes most of this funding to Integrated Care Boards (ICBs) which, in turn, plan and commission services from local NHS providers such as hospital trusts and GPs." [Public Accounts Committee]

There are no major incentives for prudent fiscal planning. As per HMT's Budget Guidance, departments and ALB's are set Department Expenditure Limits (DEL) each year. In reality, these aren't limits but spending expectations. Some underspend can be carried forward as part of a 'budget exchange'. However, this is capped at up to 0.75% of Resource DEL and up to 1.5% of Capital DEL. Furthermore, to ensure "spending power is not allowed to accumulate over time" budget exchange can only be performed from one year to the next, meaning any carry-forward from the previous year will be netted off the amount that can be carried forward into the next year. This means any unspent budget, outside of these tight allowances, in the DHSC, NHSE and local authorities are returned, creating a 'use it or lose it' funding model. [HMT]

HMT carries out an 'end-of-year benchmarking process' to assess actual spending against budgeting and forecasts."The Treasury will take their forecasting performance into account in future decisions." The unintentional consequence is a system that punitively deters fiscal responsibility, because HMT assumes expenditure spreads linearly over different years. For example, if the DHSC, NHSE or a local authority are more fiscally efficient than their peers, then their predicted expenditure demands for the upcoming year may be less than their allocated funding. However, they're not incentivised to produce a forecast that reflects that, as the Treasury will reduce their immediate funding. But if they underspend their forecast the Treasury will downgrade their future funding, and their ability to carry forward a surplus is limited anyway. Consequently, the most fiscally efficient actors are incentivised to spend when they otherwise wouldn't have in order to protect future funding.

This is the mirror opposite of how private credit markets work, where a history of fiscal responsibility and higher current capital levels are rewarded. This perverse model of incentives runs down the entire health structure. For example, individual Trusts operate their own balance sheets, but their losses and profits are nationalised. This means that a Trust running a budget surplus is at risk of the central system reallocating their profits to a loss-making Trust. Consequently, only 11% of Trusts were forecast to make a surplus in 2024/25.

"In 2023/24, their aggregated year-end deficit had more than doubled to £1.4 billion."

But this net figure conceals the true extent of the problem because the government injected £4.5 billion of additional funding during 2023/24 and NHSE underspent against its central budget by £1.7 billion to offset Trust deficits. [Public Accounts Committee]

The financial deficit run by NHS Trusts is now forecast to be almost £7 billion in 2025/26. If the lack of incentives wasn't bad enough, the ability of Trusts to budget responsibly is compromised further by inexcusable central management performance.

"For example, DHSC and NHSE have repeatedly failed to provide information about budgets in good time to local NHS systems and indeed in some cases not until months after the start of the financial year. This disregard for basic principles of sound financial planning is hampering NHS systems' ability to deliver services for their local areas." [NHS Financial Sustainability]

Moreover, after the national budget is divided and dispersed across the structure of the health ecosystem, individual Trusts and local authorities may dispute the division of financial responsibilities, such as who will pay the fees for commissioned private providers treating any individual patient. This system is entirely redundant, as all services and responsibilities are ultimately paid for by the taxpayer. But these local conflicts waste clinical time, require employment costs for management and may even incur fees for outside legal representation.

It can also create friction in the delivery of treatment for patients. Whilst referrals across ICS boundaries are not outright banned, there are often administrative hurdles such as establishing funding or contractual arrangements. Managing efficient service delivery, by referring to providers with the greatest spare capacity, is therefore hindered by the fact there are as many as 42 Integrated Care Systems within England. This can even lead to unnecessary repetitions of primary care appointments, as patients try to visit another GP or hospital in a different ICS.

Finally, like all government departments, the NHS and local authorities operate almost entirely on a one-year budget forecast. From an internal perspective, such short-term planning exacerbates the aforementioned wasteful budget practices.

But from an external perspective, this seriously limits the ability of the private sector to competitively collaborate with the public sector. Unless you are providing a service relating to long-term CapEx or are a member of a multi-year tendered framework, a commissioned private provider will only be able to forecast a maximum of 11 months of future income. This makes it very difficult for private providers, such as social care businesses, to raise capital against future income, thus increasing the barriers to entry in an already uncompetitive market.

Private sector collaboration with the state on healthcare is very significant. The value of NHS commissioning from the private sector in England alone was roughly £13 billion in 2022/2023. This is in addition to the nearly £40 billion spent by local authorities on social care, which is "predominantly privately provided." [DHSC]

-

Capital investment has been neglected in the health system for over a generation, with health funding almost entirely swallowed by staffing and day-to-day spending.

For 2024/25, the capital budget allocation was only £8 billion in total, which was already an increase on the 2010-19 average of £3 billion per annum. The CapEx budget is split into:

£4.1 billion operational capital funding for ICSs.

£3.9 billion reserved for national funds and programmes [NHS Providers]

Despite the CapEx allocation occupying less than 4% of the overall health budget:

"The DHSC and NHSE have become addicted to moving money from capital to revenue to cover day-to-day pressures." [Public Accounts Committee]

Between 2010-19 the NHS transferred £4.3 billion from capital budgets to cover day-to-day expenses. Long-term investment in the NHS estate was sacrificed to manage daily spending pressures, leading to a significant deterioration in NHS buildings and equipment by the time COVID-19 hit. This figure also doesn't account for any underspends of the remaining capital budget in those years. [NHS Providers]

In 2023/24, they transferred a further £0.9 billion from the capital budget for day-to-day spending. However, new HMT rules means they will no longer be able to do this in the future. [Public Accounts Committee]

But even if we assume Capital budgets will be respected henceforth, this won't be enough to recompense the growing backlog of capital needs due to the previous lack of investment. From crumbling hospital buildings, to a lack of both quantity and quality of machinery equipment like CT and MRI scanners.

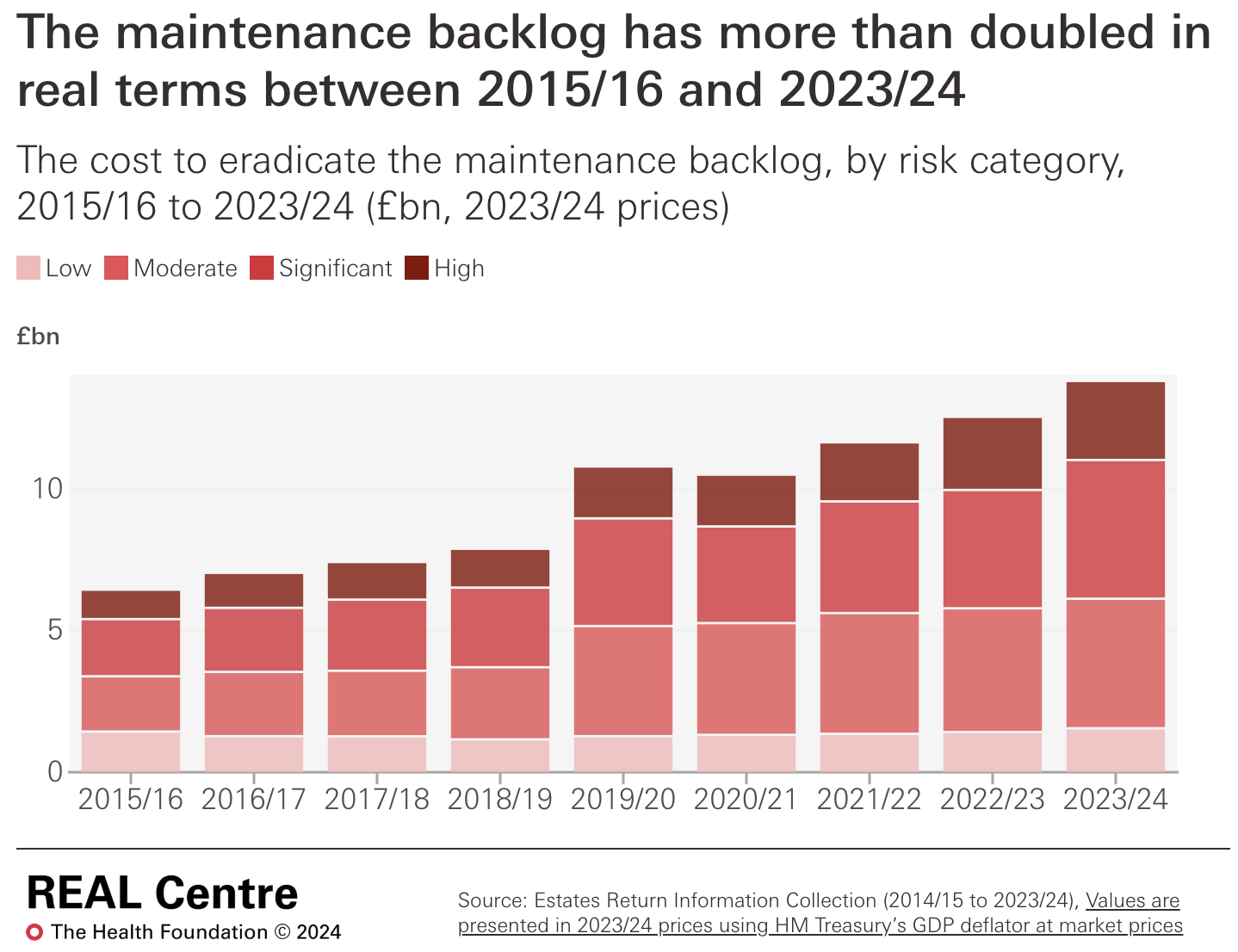

"The total maintenance backlog is currently estimated at £13.8 billion, which represents an increase of £2.2 billion from 2022/23." [NHS Providers]

This is up from a total backlog maintenance of £6.5 billion in 2018/19. ‘Backlog Maintenance’ "is a measure of how much would need to be invested to restore a building to a certain state based on a state of assessed risk criteria. It does not include planned maintenance work (rather, it is work that should already have taken place) … High or significant risk maintenance now makes up 55.5% of the total." [NHS England Digital]

The UK historically invests less in healthcare capital compared to other OECD countries. Between 2000-2017, UK healthcare capital value decreased by 3% in real terms while other countries saw increases. Countries like Austria and Denmark invest significantly more, with over five times the value of machinery and equipment per health worker compared to the UK. [NHS Providers]

In the UK between 2010-2017 "the value of health care capital has fallen by 11 % [in real terms] which has coincided with the decline in health care capital spending." Whereas, the average European country has increased the value of their healthcare capital by 20% in real terms 2010-2017. [The Health Foundation]

"The falling value of health care capital combined with an increase in health care workers means that capital per worker in the UK has fallen by 35 % [in real terms] since 2000, a far greater fall than any other [European] country." [The Health Foundation]

The value of healthcare machinery and equipment per worker was less than £5,000 in 2017, when the European average was over £20,000. Between 2000-2017, "the UK had the lowest value in every year since 2006". [The Health Foundation]

"About a third of NHS trusts in England are using “technically obsolete” imaging equipment that could be putting patients’ health at risk … Coroners have also raised concerns over the national and local shortage of radiology staff, and insufficient CT and MRI scans. Dispatches looked through five years’ worth of prevention of future deaths reports for those where a lack of radiology kit or staff was mentioned. It found 48 reports between 2016 and 2021 that mentioned a lack of scans and/or radiology staff in relation to the death of a patient." [Guardian]

-

[1.1] Create a legal requirement for DHSC/HMT to issue guidance and meaningful indicative budgets to health systems for the upcoming financial year before the end of the calendar year, and require DHSC/HMT to approve final budgets before 6th March.

"To budget effectively, ICBs need early sight of guidance and certainty about how much money they will have. In 2022/23 and 2023/24, NHSE did not approve ICBs' financial plans until June and May respectively, months after the financial year had begun. For 2024/25, planning guidance about how much funding would be available to ICBs was not released by NHSE until a week before the start of the financial year, due to delays in agreeing priorities and a final budget with DHSC and wider government. [Public Accounts Committee]

[1.2] In addition to approving final budgets for the forthcoming financial year by the 5th March, HMT should also issue indicative budgets for each of the 4 years thereafter by this date.

An effective health system requires long-term planning. But the nature of politics has meant that the system’s leadership has been short-termist. The country has experienced 14 different Health Secretaries in the first 25 years of this century, 7 of which have held the post since the Covid-19 pandemic began.

Provisional budgets would shift the planning horizon for the entire health system from 12 months to a 5 year period.

[1.3] Provide a ring-fenced emergency capital budget to clear the backlog maintenance by the end of the parliament.

In addition to the standard capital budget, create a temporary emergency capital budget that will fund the eradication of the maintenance backlog by the end of the parliament. This would require ~£14 billion (not including the cost of any additional growth in the backlog). The urgent need for this is based on safety grounds, for both patients and staff, with £7.5 billion of this fund required to cover the High and Significant Risk maintenance backlog alone.

The actual maintenance would not have to be completed to be cleared from the maintenance backlog, as the measure does not include planned work, so this is an attainable target for the end of the parliament.

Jim Mackey, interim CEO of NHSE, announced in June that they plan to deliver a new ‘off balance sheet capital investment mechanism’ by the end of this summer.

[1.4] Create a definition of ‘prevention spending’ and publicly measure it.

Growing the health system’s provision of preventative care is a crucial priority, with preventing sickness set as one of the three core focuses for the 10 Year Health Plan.

"Both DHSC and NHSE see the 10-year health plan as an opportunity to crystallise their prevention ambitions, but the lack of a precise definition of what even counts as prevention spending will make assessing progress against this vital policy aim impossible." [Public Accounts Committee]

Being able to track preventative health will also help the public to hold the government to account for progress in this area

[1.5] Establish one-way funding models. The losses of a Trust remain nationalised but fiscal surpluses should be retained by the individual trust to incentive fiscal prudence.

This would involve the abolition of the budget exchange cap for health bodies, which currently limits budget surplus carry forward to 0.75% of Resource DEL and 1.5% of Capital DEL per year. [HMT]

[1.6] Introduce billing receipts for patients after receiving treatment.

Having access to the estimated cost of a treatment would be a valuable tool for both decision-makers and the public.

Internally, generating and tracking a cost-per-action would help to inform which areas need innovation or more investment. Externally, patients would quantitatively see just how much they benefit from the free at the point of use system. It may also help the drive to preventative health, if the public have a greater understanding of the taxpayer burden of health treatments. The final bill would ultimately come to £0.00, with a 100% discount provided by general taxation.

These estimates could be calculated automatically and delivered cost-efficiently through digital provisions like email and the NHS App.

Staffing

“People, ideas, machines - in that order!”

Colonel John Boyd

-

Health and social care services are labour intensive by nature.

"In 2022/23, the total cost of employing the staff in the NHS was £71.1 billion – 45.6% of the NHS budget." [DHSC]

This doesn’t include salaries for GPs (who are not directly employed by the NHS), employees in the DHSC and NHSE, or workers in private provisions like social care. [The King's Fund]

According to the NHS workforce plan (2023), the NHS is preparing to increase its staff from 1.5 million to nearly 2.4 million by 2036/37, just to maintain current service levels. The IFS estimates that this would increase the NHS share of public sector workers from 38% to 49%. To fund the increase in staff alone would require a real term annualised budget increase of 3.6% or 70% total by 2036/37. Furthermore, this increase would only be capable of maintaining current service levels provided it was combined with generous productivity increases:

"By the NHS's own estimates, the staffing increases contained in the plan will only be enough to meet NHS demand if productivity can be increased by between 1.5% and 2% per year: an extremely ambitious target well above what the NHS is estimated to have achieved in the past. The Office for National Statistics estimates that quality-adjusted productivity in the NHS increased by an average 0.8 % per year between 1995/96 and 2019/20." [IFS]

This presents a fundamental problem in the face of two growing pressures: the increasing demand for services and the increasing cost of employment.

-

According to the ONS, between 1997-2022 the UK population increased from 58.3 million to 67.6 million and is projected to increase further to 76.6 million by 2047. In addition we also have an increasingly ageing population, with the ONS projecting that between 2022-2047 the number of pensioners will grow by 25%, whereas the working age population will only grow by 16%. [ONS]

This has translated into growing demand for health services. Between 2008-2019, the number of outpatient appointment referrals increased by 3.2% per year. The health system is also having to adapt to the disproportionate growth of mental health conditions:

An NHS survey of children and young people’s mental health found that between 2017-2023 the proportion of children with probable mental disorders increased from:

12% to 20% (children aged 8 to 16)

10% to 23% (teenagers aged 17 to 19) [HofC Library]

With such an increasing rate in the demand for health services, adequate staffing has struggled to keep up. According to the BMA, between 2015-2025 the number of patients per full-time GP has gone up by over 16%, whilst the total number of GP practices has reduced by over 18%.

"The number of available consultant-led beds in England has halved over the past 30 years." [The King's Fund]

"The average number of doctors per 1,000 people across the EU members of the OECD, for which data is available, is currently 3.8. Germany has 4.5. England, by comparison, has just 3.2 and would need an additional 40,000 doctors to reach the OECD EU average.” [BMA]

“There is also significant regional variation in the distribution of doctors, with some areas falling even further below the OECD EU average. The East of England, for example, has just 2.5 doctors per 1000 people." [BMA]

"The number of practice nurses has hovered around the 24,000 mark for several years." Of this, 7 out of 10 work less than full-time, and 33% are over 55 years old. In certain specialist areas there has been a significant reduction in numbers. For example, between 2010-2023 the number of learning disability nurses decreased by 44%, and the number of district nurses and community matrons fell by nearly 45%. [Nuffield Trust]

This has produced a worryingly large vacancy list.

There were 125,572 vacancies in the NHS between March and June 2023. The NHS may have had some 1,400 unfilled doctor vacancies and around 8,000 to 12,000 unfilled nursing vacancies on a given day. [Nuffield Trust]

There are currently 8,330 secondary care medical vacancies in England (April 2025). [BMA]

The national vacancy rate for NHS general dentists is 21%, with 2,749 full-time vacancies. [DHSC]

The NHS is currently short of nearly 2,000 radiologists, with 1 in 10 radiology jobs unfilled. The shortage of radiologists could reach 6,000 by 2030. [Guardian]

The current shortage of 200 clinical oncologists could triple to 600 by 2030.[Guardian]

The social care sector estimates the workforce will need to increase by almost a third by 2040 just to keep pace with the aging population - equivalent to more than 500,000 new posts. [IFS]

Minimum staff requirements for any given service are set by the relevant ‘independent’ regulator. However, many NHS wards operate below full capacity because efficient patient allocation is limited by the funding processes, but the legal minimum staffing requirements to operate a ward remain the same.

For NHS Trusts, they rely on agency staffing, which are several multiples more expensive (3-5x). Data from ~50 NHS trusts suggest that in May 2021, an estimated four in five registered nurse vacancies and seven in eight doctor vacancies were being filled by temporary staff, either through an agency or using their ‘bank’ (the NHS in-house equivalent of an agency). The NHS is forecast to spend over £10 billion on temporary staffing in 2025/26.

As their losses are covered by the taxpayer, there is no real incentive to efficiently plan staffing. However, this is untenable for private providers, causing private markets to concentrate. 75% of the private hospital market in the UK is made up of just 5 providers. The care home market has over 6,000 providers, but the largest 10 comprise ~18% of the market.

-

In 2010, the National Minimum Wage for a worker aged 21+ was £5.93 per hour. Since then it has increased at double the rate of inflation, now standing at £12.21, representing an increase of over £13,000 per year for a full-time worker.

On top of this, in 2010/11 the rate of employer's NICs was 12.8%, which was then increased to 13.8% in 2011/12. Then on the 6th April 2025, the rate of employer's NICs increased further to 15%, and the salary threshold was reduced from £9,100 per year to £5,000. The government has committed not to increase the new threshold with inflation until at least 2028.

In 2012, Automatic Enrolment in Workplace Pensions was phased into practice. The legal minimum employer's contribution was initially set at 1%, but was increased to 2% in 2018, and then to 3% in 2019.

Then in 2017 a new employment tax was introduced - the apprenticeship levy.

"The levy is applied to employers with a total annual wage bill of more than £3 million. The levy is 0.5% of the total wage bill, with an allowance of up to £15,000 to set against the tax. In other words, it is a 0.5% levy on wages in excess of £3 million … Despite its name, the levy has very little meaningful connection with apprenticeships … Only about 2% of employers have a wage bill high enough for them to pay the levy, but they employ a majority of all employees. The tax is forecast to raise £4 billion in 2024/25." [IFS]

This growing cost of employment has translated into higher fees across the medical industry. In social care for instance, between 2015-2024 fees to local authorities increased in real terms by:

33% for old people's care homes

18% for home care

13% for working-age adult's care homes [The King's Fund]

It has also reduced experience based pay differentials. "In March 2016 care workers with 5+ years experience received a 4.4% premium (33 pence per hour), but by 2023 this had fallen to just 0.6% (6 pence per hour)." [IFS]

The higher fees, driven by the increasing cost of employment, have been particularly exacerbated in social care by the drastic reductions to local authority funding during austerity. Today, the spending power of local authorities remains lower than in 2010/11 in real terms.

"But local authorities have a legal duty to set a balanced budget and that meant less money was available to spend on meeting the increasing levels of demand they faced.

As a result, between 2015/16 and 2021/22 the number of people receiving long-term care declined from 873,000 to 818,000. The loss was largely felt by older people: the number receiving long-term care fell from 587,000 to 529,000.

The chain was only fully broken last year (2023/24) when a significant increase in local authority spending power meant they were able not just to pay higher provider fees but also to increase the number of people they supported." [The King's Fund]

-

[2.1] Resolve the structural stagnation of real wages in the NHS by permanently rebalancing the remuneration packages for all staff:

Only 1/3 of NHS staff are content with their pay. Despite a 6% pay increase for doctors in 2024, both Consultants and 2nd year Foundation Doctors were paid 11% less in real terms in 2024 than they were in 2010. [The Health Foundation]

But (after the administration charge) the employer pension contribution in the NHS is 23.7% (14.38% contributed directly by the employer and 9.4% by NHSE). By reducing the employer contribution down to 10% (of the new higher salary), this would fund a pay increase of ~12.45%. Employees would still have the freedom to put all of that increase in their pension tax free, as if nothing has changed.This would still provide an incredibly competitive employer pension contribution. The legal minimum employer pension contribution is 3%. The average private sector employer pension contribution was ~6%in 2021. The average employer contribution in the H&SC sector was 8.6% in 2022.

[2.2] Movement of pensions from defined benefit to defined contribution.

Under current defined benefit pension schemes, the future taxpayer is liable for funding 100% of private sector pension pots. By moving to defined contribution schemes with employee and employer contributions invested in the market. This would mean the majority of eventual pensions would be funded through compound interest, and taxation would only fund employer contributions.

This will mean public sector pension values will be vulnerable to negative market forces, so they are less protected than they are now. However, this is what everyone in the private sector has to accept.

[2.3] Commit to increase the cap on university medical places in England by at least 1,000 every year for the rest of the parliament:

The NHS workforce plan aims to double the number of medical school places by 2031/32, along with increasing GP training places by 50% and increasing adult nursing training places by 92%. As a consequence, they forecast that the share of NHS staff recruited from overseas will fall from nearly 25% to around 10% by 2036/37. [IFS]

But in the three years since the NHS Workforce Plan was published in June 2023, medical places have barely moved.

"Under the previous government, 205 and 350 additional medical school places were allocated for the 2024/25 and 2025/26 academic years respectively. This brings the total number of government funded medical school places for the 2025/26 academic year to approximately 7,800." [DHSC]

This means they'll have to increase the cap by over 1,000 each year just to meet the target in the NHS Workforce Plan (which only prepares to maintain current service levels).

In 2023 the government said the cap exists “to ensure teaching, learning, and assessment standards are maintained.” But the NHS lost between 15,000 and 23,000 doctors in the year 2022/23 alone, so medical places are not even sufficient to meet replacement levels.

Expanding teaching capabilities is cheaper in the long run than artificially limiting medical places and then relying on overseas staff to fill vacancies.

[2.4] Permanently reshape the Health system's relationship with temporary staffing:

Introduce a licensing condition, preventing medical-staffing agencies from supplying the NHS with temporary staff that were trained by the NHS until at least 5 years after qualifying. This is not as restrictive as introducing a minimum period-of-service clause following training, as that may deter people from training in the first place. Newly qualified medical staff would still be free to work in the private sector, abroad, or in a different industry after qualifying. But NHS trained staff should be prohibited from leaving just to be rented back to them at extortionate rates by agencies, before the NHS has even had the chance to recoup the cost of training.

Create a central registry for vetting the qualifications of all temporary staff used by the NHS. Each agency would have to log each individual staff member with the central registry, who would set qualification equivalence rules.

New central vetting registry would carry out spot worker skills assessments/simulation tests to ensure temporary staff meet minimum quality standards, and spot agency audits/inspections to ensure the agencies have checked credentials and references of all staff. Currently, there is no temporary workforce registry which can track the performance of temporary staff across different postings in the NHS. Shift allocation of temporary staffing should then be linked to their profile on the vetting register.

Increase penalties for staffing agencies for breaking rules/failing audits, including public delisting and prevention of work visa sponsorship abilities.

[2.5] Extend the NHS exemption to the April 2025 NICS changes to private Health & Social Care providers:

The changes have increased employer national insurance contributions by over £1,000 per full-time employee on minimum wage, and by over £1,600 per full-time employee on median earnings. H&SC is particularly labour intensive by nature e.g. consider individuals in social care that require 24/7 residential support, with 2:1 staffing needs. Even for small to medium sized providers, this has added hundreds of thousands of pounds to their annual costs.

Whilst the additional cost of employment is ostensibly proportional to the size of a business, the tax changes will have a regressive effect on the composition of private markets. This is because smaller providers have weaker profit margins, in the absence of economies of scale where they can spread fixed costs across a wider revenue base. As smaller providers will struggle to absorb the additional costs, it will accelerate the existing concentration of private health markets.

For example, the adult social care sector was made up of 18,500 providers in 2023/24, employing over 1.7m people. But 15,700 of those providers employed less than 50 people each, with roughly 60% of the sector’s workforce employed by the largest 7% of providers. [Skill For Care]

[2.6] Introduce a placement trading system for final year medical students, allowing them to agree to swap the location of their two year foundation training:

The system for allocating foundation training placements was recently changed. Previously, there was a merit based system to allocate locations, with students ranked based on a mixture of academic performance, a situational judgement test, and relevant extracurricular work. This was deemed to place additional burden on medical students in their final year.

The new ‘preference informed allocation’ randomly applies a computer generated rank, after asking them to submit their preferences. The algorithm then works through the applicants in order. If their first choice is still available, that is what they are allocated, but if their first choice is full then it skips past you. After rotating through, it returns to unallocated students and places them at their highest preferences location.

The results for this have been mixed. The proportion of students being allocated their first preference has actually increased, marginally, from 71.02% in 2023 to 75.42% in 2024. However, 2023 was an unusually low year, and 75% seems to be a return to the previous norm. More importantly, the proportion of students being allocated a location in their top 5 has decreased to 90.24% from a historical average of ~95%. So there is a 1 in 10 chance medicine graduates have to train for two years in a location outside their top 5 preferences.

Many will ask for a return to the old system, but it is true that this placed additional burden for final year medicine students. It is difficult to base the allocation purely off university academic performance due to the varying quality of different university grades.

Instead, a new post-allocation system could be introduced to enable two consenting medicine grads to swap their placements.

Performance Management

“Management is doing things right; leadership is doing the right things.”

Peter Drucker

-

…

-

…

Digital Infrastructure

“Necessity is the mother of invention.”

Ester Boserup

-

…

-

…